Nothing in the Basement Sample Chapter 13

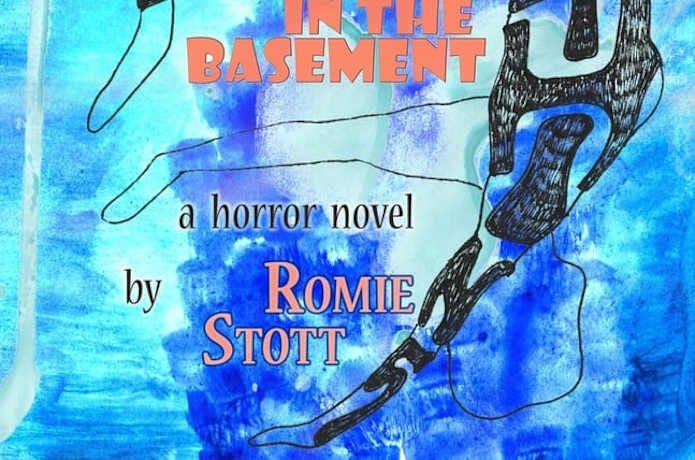

New Dybbuk Press Book by Romie Stott

It’s been over 11 years since the last Dybbuk Press book, King David and the Spiders from Mars. It’s been a rough decade. I had to take care of my dying mom and moved her to a nursing home in NYC where Cuomo’s bullshit killed her. A few years after Covid, ChatGPT killed my best income stream because why pay someone to write your term paper when AI does it for free. So it’s been a mess.

Happily, Romie Stott had a great horror book about a married couple dealing with a malignant house that is collapsing around them. It’s a slow burn that ramps up the tension in so many ways. I’ve had a working relationship with Romie since I first read her story for She Nailed a Stake Through His Head. It was one of those stories that every acquisitions editor craves, the kind of story that announces itself and makes the editor go “I need to publish this before anyone else gets it.”

So I am very excited to publish the new Romie Stott book. It’s available for sale on September 2. You can buy advance copies at Bookshop. If you’d like a signed copy, please donate to the Indiegogo Campaign.

Look at it one way, and Romie Stott's Nothing in the Basement is a sharp, occasionally ironic, scrutiny of two middle-class, middle-aged people, living in a money pit of a house at peak midlife crisis. It is also a story of the slow decay of environment, relationship, and sense of self. Domestic entropy, but make it haunted. Sometimes it was so startling or frightening, I gasped out loud. The reader seesaws between appropriately appalled sympathy and an odd schadenfreude that is so jubilant and malicious that it must come from without, not within. Surely this book has possessed us.

- C. S. E. Cooney, World Fantasy Award-winning author of Saint Death's Daughter

Chapter 13

Sandra had watched a nature special some years before. A zoologist had explained animal tracking, including how to make guesses about an animal based on its spoor. Carnivores had long, snaky, continuous excretions; herbivores left piles of soft round pellets. Ever since, Sandra had examined her bowel movements, and judged how they tallied with the previous day's proportion of meat to vegetable. She liked the brief excuse to think about how her body worked and moved and made energy; she liked to think of herself as an animal, because she liked animals. (She often watched on-line videos during work hours, and forwarded the cuter examples to co-workers.) In the bathroom, in front of the toilet, she forgave herself. Then she flushed.

Lately, the act of flushing had taken on a certain suspense, and justified Sandra's special attention. Thus far, the house's toilet had responded well to plunging. It would need a good snaking soon. Sandra only put it off because she dreaded what else a plumber might recommend. The waterworks of an old house held mystery and power in the same proportion as her reproductive organs. One could either ignore them or blame them for everything. The idea that the plumbing might ever work perfectly seemed ludicrous. Most workmen made her feel guilty - either furious with herself for agreeing to work she didn't believe in, or nervous that she was bullheaded, stingy, cynical, and oblivious to risk. As she plunged, she plunged the rhythm of TMI. Plumbers and doctors gave too much information about systems she couldn't control. A cause without symptoms was no cause at all. Expert talk about causes always struck her as men showing off - a display of power and entitlement. As much as Sandra disbelieved all forms of women's intuition and the magical power of mothers, she had to admit that they worked as a bulwark against the flood of male expertise. You want irrational? I'll show you irrational. I can do magic, and you can't even tell.

The sound of Sandra's plunging carried into Robert's dreams. It hadn't made sense to him to go into work for the few hours before his dentist's appointment. He was snoozing luxuriantly, even though he knew gradual waking only made him sleepy and low-spirited for the rest of the day. In his dream, Robert was trying to drive a car out of a flood - a blue 70s-model Citroen with a sticky gearbox. He had to divine the road from landmarks - avenues of trees, the top of a hydrant, the hump of a mailbox. Sandra sometimes sat in the passenger seat, quiet and pale, hands tight around a precious object. At other times, she was gone. Dark water obscured the surface of the road. When Robert drove over something, it shredded his tires and crippled the car. He could neither see it nor guess what it was.

The emptiness beneath the house had no thoughts or motivations. It worried the dogs. When you dig a hole, you make a hole. A house was enclosed. The nothing frightened the dogs because it helped no one and belonged to no one.

Chapter 14

The dentist could not explain Robert's decoupled teeth.

"Could it have been a problem with the batch of dental cement?" asked Robert.

"Could be," said his dentist.

"Or maybe I ate something and it reacted somehow. Maybe I'm constantly eating or using something, like baking soda in my toothpaste, or acai juice - it's in everything now; you can't escape it - or bergamot, and it's been slowly dissolving this whole time, only the cement adhered so well that everything stayed secure until it was all gone."

"Could be."

"Then how do you know it won't happen again?"

"I don't think it will," said the dentist.

"This has been very embarrassing for me," said Robert.

"How about if it falls out again, I'll fix it again, free of charge?"

"Well… I'd still rather it not happen." A weak joke. The dentist smiled, but he smiled out of politeness. The dentist made some notes.

"Do you think it's the motorcycle?" asked Robert.

"I do not," said his dentist.

What the dentist did say was that the x-rays showed bone loss unrelated to the trouble with the bridge, and that Robert needed to floss more carefully and use prescription fluoride toothpaste. Maybe come in for another checkup in three months to see whether a periodontist needed to get involved. He pointed out on the x-ray where Robert's roots didn't go so deep - "that's nothing you're doing wrong - it's just how your teeth are, and it puts you at greater risk than some people.”

He drew circles around small dark pockets below the ghostly image of gum line, places where Robert's jaw was receding.

"I wouldn't worry about it, though," the dentist said. "Just keep an eye out."

When Sandra got home, Robert met her with a big smile and a picnic basket. This was a risk - she did not like most surprises. She was delighted. They piled the dogs into the car and drove to the park to watch the sunset while Pilgrim ran after squirrels. When Sandra curled up against Robert's shoulders, he felt taut like a hot air balloon, filled with pride and half a bottle of wine. He'd made all good choices, from the right salad dressing to the decision not to talk about the dentist. (The jaw pockets would only worry Sandra.) He was a god.

"We never do stuff like this anymore," said Sandra. "What brought this on?"

"I love you, and I think it's crazy that we don't do things like this anymore. Why not be newlyweds forever?"

Sandra snuggled in closer. Another right answer. In his head, Robert floated above the countryside. The grass below spelled out an infinite scoreboard, full of his initials

As usual, I am an editor and a writer who makes a living (haha) off of editing and writing. If you want to support me, please donate to my gofundme, get a paid subscription or hire me to edit or write what you need (term papers, resumes, personal statements, etc.) at omanlieder@yahoo.com or

Again, you can buy advance copies at Bookshop. Part of proceeds go to Strange Horizons.

If interested, please donate to the Indiegogo Campaign.

You can buy more Romie Stott books at Amazon.