"O Youth and Beauty" (The Stories of John Cheever)

“The pistol went off and she got him in midair. She shot him dead.”

By the time Cheever wrote this story, he was fully immersed in the suburbs. Say goodbye to the well-crafted New York stories. Suburban Cheever is messy and chaotic. Even though the plot is fairly straightforward and the characters familiar, Cheever's talents are on full display. The Cliff Notes summation (aging athlete tries to relive glory days and dies hilariously) cannot begin to describe the glorious weirdness.

The Opening Sentence

Most editors and grammar apps want short punchy sentences. If a sentence lasts longer than 12 words, Microsoft Word automatically gives it a “run on sentence” note. Everyone is trying to win a Bad Hemingway contest. Under the rubric of clarity, Raymond Carver allowed Gordon Lish to rip the heart out of his stories. In that context, enjoy this beautiful sentence for audacity alone.

“At the tag end of nearly every, long, large Saturday night party in the suburb of Shady Hill, when almost everybody who was going to play golf or tennis in the morning had gone home hours ago and the ten or twelve people remaining seemed powerless to bring the evening to an end although the gin and whiskey were running low, and here and there a woman who was sitting out her husband would have begun to drink milk; when everybody had lost track of time, and the baby-sitters who were waiting at home for these diehards would have long since stretched out on the sofa and fallen into a deep sleep, to dream about cooking-contest prizes, ocean voyages, and romance; when the bellicose drunk, the crapshooter, the pianist, and the woman faced with the expiration of her hopes had all expressed themselves; when every proposal – to go to the Farquarsons' for breakfast, to go swimming, to go and wake up the Townsends, to go here and go there – died as soon as it was made, then Trace Beardon would begin to chide Cash Bentley, about his age and thinning hair.”

No word is wasted. No clause is unnecessary. Every part works, even the length gives the reader the feeling of spending too much time at a party. Just as a conclusion seems imminent, a semi-colon breathes new life into it. Only after the babysitters and the early morning golfers and the failed ideas, do we get Cash Bentley. Had the story begun with Cash Bentley moving the furniture to run around his obstacle course, it wouldn't have the same power.

Forgive the film analogy, but most writers want to give the reader the fast cut MTV inspired sentences. This is the equivalent of the Goodfellas kitchen tracking shot.

Shady Hill

Without Shady Hill, Cheever would have been indistinguishable from Updike or Carver or Salinger. His stories would have been clever, but cold. Shady Hill gave him license to delve into the bizarre world of cul de sacs and neighborhood parties. John Waters said that New York is full of normal people who think themselves unique while Baltimore is full of weirdos who think that they are ordinary.

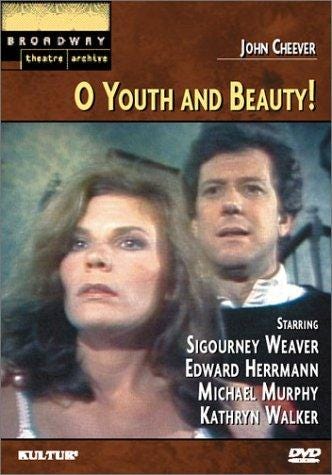

Cheever's Shady Hill is an ostensibly normal 1950s normal suburban community. Men commute work and women stay home to boss around the servants. Everyone is drunk. Below the surface, the residents are unraveling in their own ways. The Farquarsons host parties. Mrs. Henlein watches the children. In the 1979 adaptation, the Lawtons (played by Ed Hermann and Sigourney Weaver) from “The Sorrows of Gin” show up at Cash's hospital room with booze. The pressure to conform breaks everyone and their misery gives the reader hilarious drama and sad comedy.

“The Good Old Days”

Cash Bentley is a familiar character. If you've been on social media and had the misfortune of following an unhinged cousin or someone you knew in high school, you've seen Bentley Cash in action. He's the 1950s equivalent of the sad boring bastard reminiscing about high school or posing memes about how wonderful life was before cell phones and TikTok took over. He peaked in high school. He truly believes that adolescence is the “best years of your life” because in his experience, that dumb statement is true.

He remembers how he was once an athlete. Everyone loved him. He went to the best parties. People paid attention to every inane word coming out of his mouth. He didn't have to learn or grow as a person. Once he stopped running, he didn't do anything worth mentioning. His businesses failed. His marriage is miserable. Forty year old Cash is very much like 18 year old Cash. His life revolves around parties and impressing his friends by running and jumping. The main difference is the fact that 40 year old Cash is incredibly sad. Also he's been drinking and smoking and clogging his arteries for decades.

When he breaks his leg, he can't run his way around his vague disappointment. He drinks more. He picks fights. The neighbors stop inviting him to parties. Because he can't run around their living rooms, he can only offer asshole behavior. He goes to dances and tries to dance with young girls who run away. By the time he recovers enough to run another obstacle course, he's winded and he looks like hell. Yet, what else is he going to do with his life?

History renders Cash Bentley even more pathetic. He's a 40 year old man in 1953, nostalgic for his 20s. His good old days were the worst years for America. The Great Depression was at its height. People were losing their homes and jobs in record numbers. Banks were wiping out life savings. European nations were turning fascist. Cash Bentley doesn't care about any of that. He only cares about the time when he could run fast and hit on young girls without censure.

Women

Cheever was not a feminist writer. He was too enamored with sad white guys. Yet, when he wrote women he wrote complex characters negotiating with a misogynist society. Louise Bentley, Cash's wife, is living in a 1950s traditional marriage and she'd love to be in a 1950s marriage. Only she's living with a man who is a teenager with teenage drives and anger in the body of a desiccated 40 year old man.

Louise isn't a brilliant homemaker. Most of the time she doesn't even cook. She wants a job. She wants something more. At very least, she wants to get out of the house and leave behind the expectations of free labor in the form of endless cleaning and cooking duties. Instead, she's trapped in a cycle of tedious arguments, avoidance and make-up sex. Every time her friend actually finds her a job, she is in a point of reuniting with Cash and eager to give the marriage another shot.

Pun possibly intended.

The Ending

For the fourth time in the story, Cash tries to run the obstacle course. He rearranges his own furniture. He gives Louise a pistol, not a starter pistol. He doesn't show her how to work the safety. He just tells her to shoot in order to start the race. She fumbles with the gun. He starts running anyhow. Then she finally gets the safety off and we are treated to very short sentences.

“The pistol went off and she got him in midair. She shot him dead.”

That's all folks.

Yes, other writers kill off the protagonist in the ending. It's a Creative Writing 101 cliché. Salinger ended “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” with Seymour Glass shooting himself in the head. Only Salinger was sprinkling that story with clues about Seymour's growing dissatisfaction.

Yet, few writers are having this much fun with that death. Cheever leaves the reader with the question of why Louise shoots him. Was it an accident or on purpose? If it was on purpose, was it a mercy killing or was she just sick of Cash's bullshit? Either way, mazel tov. That guy was the worst.

Sadly, I can’t find the Alfred Hitchcock Presents adaptation online, but there’s a link to the 1979 PBS adaptation of this story.

I also publish books through Dybbuk Press, here’s one called BADASS HORROR.

What a lovely analysis of that story. I used to love Cheever, when I wrote fiction. I need to reread him. His son wrote a book called The Plagiarist and came to my class in grad school. He seemed crushed by people constantly comparing him to his father.