John Cheever lived for a year in Italy in an apartment in the palace of Princess Orietta Pogson Doria Phamphilj. He drank. He went to parties. He complained about the clogged drains and gas leaks. In this story, Cheever writes about her through a character named Donna Carla Malvolio-Pommodori, Duchess of Vevaqua-Perdere-Giusti, etc. The “etc.” is intentional. Cheever uses her life story as road map. Both the real Princess Orietta and the fictional Donna Carla share life events including:

Her father was Italian nobility

Her parents met when her nurse mother helped her father recover after a life threatening accident.

Her nurse mother was more interested in the trappings of nobility than her father.

Her father openly hated Mussolini

The family had to go into hiding when the Nazis invaded post-Mussolini Italy.

She takes care of her parents

The family has an impressive art collection

As soon as her parents die, she marries a working class man that she's known for years.

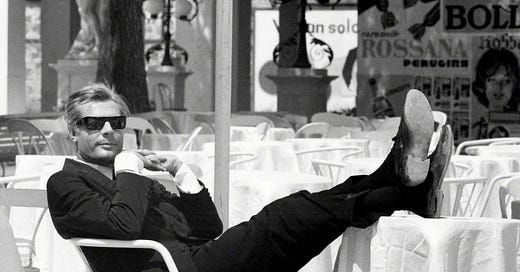

However, John Cheever is not writing a straight biography. The Duchess paints the kind of scene you see in mid-20th century Italian movies. Artists pose next to the statues. Young lovers ride their Vespas past the Coliseum. He describes the duchess walking out of her palace to go to mass never quite seeming to leave the grainy light. “The music that drifts down from the medieval walls into the garden where we sit is an old recording of Vivienne Segal singing 'Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered'; and Donna Carla lived, like you and me with one foot in the past.”

Even without knowing that his duchess is based on a real woman, this is a vivid character living through the most turbulent history while grounded in role of a noblewoman, negotiating the Italian culture where other nobles see her as financial salvation. “In the second year after the war, a hundred and seventeen suitors came to the palace. These were straight and honest men, crooked men, men suffering from hemophilia, and many cousins.”

Cheever outright starts the story by stating that someone from a small town in Massachusetts or a son of a coal miner would be impressed with the duchess because she's a duchess, but throughout the story, it's obvious that this woman impressed her with her strength. Did the real duchess drive a carriage to her country estate when the Communists threw rocks at her and knocked out her driver? Who knows. Certainly, Cheever depicts his fictional duchess as taking over the estate without even bothering to note the “Death to Donna Carla!” graffiti.

The funniest scene happens toward the end as one final German noble arrives to press his luck. Like most of her suitors, his castle is falling apart. His mother bathes in a bucket. He's got a mistress and a few kids, but he needs the money that a marriage to Donna Carla would give him. By this time, most of the suitors have given up and scorn Donna Carla as a selfish woman who probably starves her servants and shoplifts.

“We have much in common, Donna Carla.”

“Yes?”

“Painting. I love painting. It is the love of my life.”

“Is that so?”

“I would love to live as you do, in a great house where one finds – how can I say it? - the true luminescence of art.”

“Would you really? I can't say that I like it much myself. Oh, I can see the virtues in a pretty picture of a vase of flowers, but there's nothing like that here. Everywhere I look I see blood crucifixions, nakedness and cruelty,” she drew her shawl closer. “I really don't like.”

“You know why I am here, Donna Carla?”

“Quite.”

“I come from a good family. I am not young, but I am strong. I...”

“Quite,” she said. “Will you have some more tea.”

“Thank you.”

He leaves with respect for an eminently sensible woman, but he definitely does not get the wealthy wife he wanted. Of course, as soon as her parents are dead, she goes to her father confessor in the Vatican and tells him that she wants to marry Cecil Smith who helped to run the estate with her father before and after WWII. Cheever ends the story by saying that she is still cursed in every leaky castle in Europe.

By most accounts, Italy was a creative dead zone for Cheever. He only wrote one story the entire year. Happily, he could draw upon the experience after he returned. As much as his audience loved the Shady Hill stories, these Italian stories are certainly a fun counterpoint.

Here’s an article about Princess Orietta’s kids fighting over the artwork.

If you’d like me and want to help me out, please consider getting a paid subscription or donating to my Gofundme. Even $5 would help.

You can read The Duchess in the New Yorker if you have a subscription.