When Dorothy Parker praised a Salinger story as “urbane, clever and well-written,” it was practically the mission statement of The New Yorker. “The Hartleys” feels like a Salinger story, because Salinger is the most prominent survivor of that mid-20th century New Yorker style. That magazine truly loved clever stories by white men from New England.

Published in 1949, “The Hartleys” has all the tropes of the genre including a shocking tragic, yet thematically consistent ending, distancing viewpoint, foreshadowing and uptight WASPs hiding their emotions. This was never going to be one of Cheever's classics. It is too well written and the story feels mechanical. One of the most memorable passages from the Tao Teh Ching reads “true perfection seems imperfect, yet is perfectly itself.” Every classic from Moby Dick to Their Eyes Were Watching God to Hamlet is full of eccentricities and messy bits that should not work. Yet, readers have loved these works precisely because they are so messy and outrageous.

“The Hartleys” is impressive, but it's not the kind of story anyone loves.

The third person limited perspective is already distancing the reader from the Hartleys. All we know about the married couple is that they are going on a ski trip with their daughter and they visited the same ski lodge eight years before the story. The couple is committed to drinking and having a good time. Their daughter, Anne, does everything she can to avoid the family outing. Anne has the most personality. She is cold to her mother but openly loves her father. As long as her father encourages her to ski, she tries skiing. Yet, she stops skiing and goes back to the lodge as soon as his attention wanders.

Toward the end of the story, Cheever uses an open door fight so that another guest can hear Mrs. Hartley screaming about how it's useless to rekindle their marriage with nostalgic visits. She also preferred separation and says that Anne could always visit.

If the story was a mystery, this scene would be the big reveal. Since it's a literary story about the sad lives of privileged people, it feels like a cheat. Cheever had written these characters at such a remove that he forgot to tell us what was going on. With the distancing conceit, most readers could reach the ending without understanding that the Hartleys are in the final stages of their marriage. Without the “here's the theme” scene, the reader could assume that Anne simply liked her father better. Her actions do make more sense when you discover that she spent time in her mother's custody, only seeing her father on visitation. Presumably, Cheever got sick of hinting and outright threw in some drunk dialogue to explain the story.

Then Anne dies.

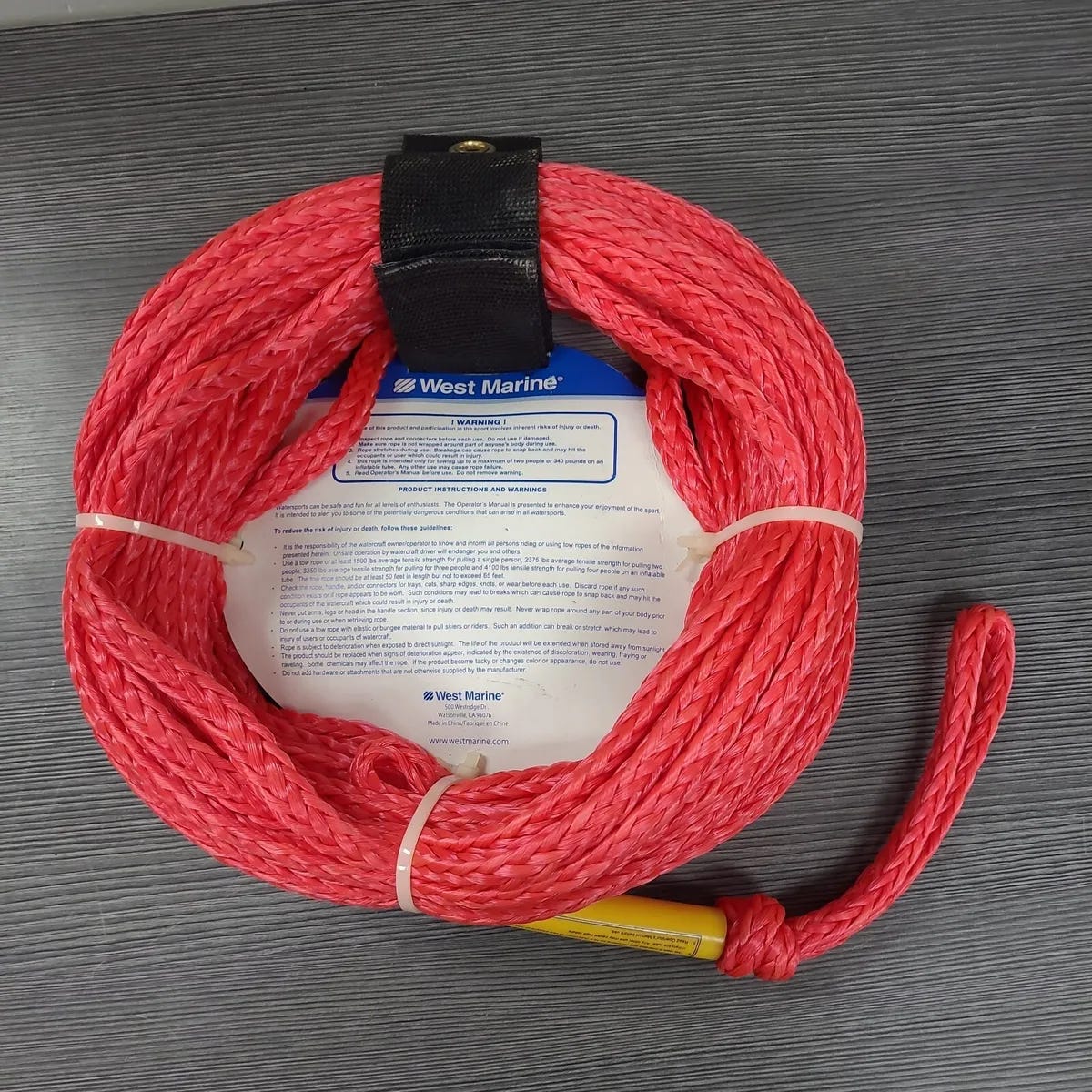

Anne's death is powerful not just because it's so sudden, but it also supports the themes. Anne is on the tow rope and her sleeve gets caught. She screams. Everyone else screams. The rope drags her to her doom and she breaks her neck. It's a tense ugly scene, rendered horrifying by the general helplessness.

Death by tow rope is not common, but it makes for great symbolism. Just like Anne was dragged along to her parents' sad reunion, she is dragged along to her death. More realistically, Anne would mangle her arm and spend weeks in the hospital, disgusted with both her parents. That might have appealed to 1960s John Cheever, but in 1949, he was a much more conventional writer. The sudden tragic child-killing ending was too attractive to resist.

The last paragraphs see the Hartleys driving home in silence. The silence is definitely effective. We learned next to nothing about these people. They were unhappy but they were probably together for their daughter. Thus Anne, the only interesting character, ends up as a symbol of a broken marriage.